(Published Fall 2016)

Whenever a catamaran wins an event, the skipper always boasts of his maximum speed …..15…20… knots….maybe more. That’s impressive, of course, but I wish there were a comfort barometer, too. A crew winning with a comfort factor of say eight and a half out of 10 would certainly rank higher in my book than a winning effort with a comfort factor of two and a half.

One thing we have particularly enjoyed about sailing our first catamaran after several decades of monohull sailing is the wide range of operator-controllable speed on a cat. We have more ability to balance speed and comfort on a passage.

As a safety factor, we can easily speed up or slow down to put ourselves in a better position to react to changes in weather. The level of discomfort on a cat increases with speed as the waves hit the surfaces of the hulls. As speed increases, the noises are louder and the motion is more erratic.

Sailing from Martinique to Dominica on a close reach in 30 knots of wind, we could have easily sailed along at 15 knots. Instead, it was much more comfortable to put two reefs in the main and slow the boat to 10 knots while watching other boats slogging to weather with full mains.

When we plan a passage, we try to consider factors that will allow us to reach our destination quickly and comfortably with a well-rested crew and without breaking gear. Whether it is a day trip or a 10 day passage, we want to arrive with energy to enjoy our destination.

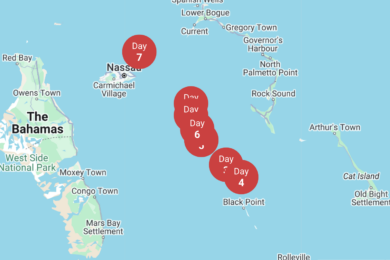

In the fall, when we leave the Chesapeake Bay for the British Virgin Islands in the Salty Dawg Rally, it is likely to be a “frontal” passage with winds ahead of the beam for at least part of the trip. When we sail across the Atlantic from the Cape Verdes Islands to St. Lucia, we expect a downwind passage.

Interestingly, in the ten plus years we have sailed to the Caribbean in rallies, the participating catamarans and monohulls generally complete the passage in about the same overall time—give or take a day. While cat owners are likely to see higher maximum speeds than a monohull of the same length, they probably will not achieve an average speed for the whole passage of more than a knot faster. If the wind is ahead of the beam and the seas are rough, most catamaran sailors slow their boats to enjoy a more comfortable ride. (If the seas are calm and the wind is behind the beam, the cats take off like a shot.)

During a frontal passage with winds 15 to 20 knots, we frequently sail with a reefed main at night to slow the boat down, reduce the noise, and allow everyone to sleep better. It is amazing how much more comfortable the boat is at nine knots than 11 knots in rough seas with winds ahead of the beam. During the day, when the crew is in the main salon or cockpit, the noise and motion issues are less bothersome, so we can shake out the reef and increase our speed without lowering the comfort quotient.

In the passage to the Caribbean, we frequently experience light air for a portion of the trip. We can sail comfortably at lower speeds in lighter air than we could on our monohull. The large reacher or genoa and full main propel the boat forward easily, even if the seas are lumpy after a front passes. We motor less which may lead us to plan for reduced overall average speed, but we are, after all, sailors.

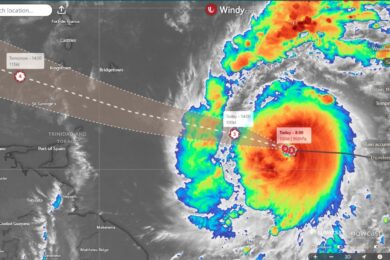

While we don’t sail fast enough to outrun weather fronts, we can often maneuver quickly enough to reduce their impact. Heaving-to is an effective and easy tactic to use on a cat to avoid unpleasant conditions.

On a downwind passage, we often sail with the symmetrical spinnaker and no main. Without the main, the boat is easier to handle and we can be ready for the inevitable tropical squall. We usually carry the chute up to about 20 knots true. Flying the chute on a cat is easy for a short handed crew since there is no pole and gybing is effortless. Our friends who have crossed the Pacific in a cat recommend a 85 percent, heavy nylon spinnaker with reinforced fittings in order to carry the sail up to 30 to 35 knots again, without the main.

At the end of the day, we can get there fast with a high comfort factor and ready for the adventures that our destination offers us.

Julie Palm has made a circumnavigation with her husband Rick and they have worked with the Carbbean 1500 and the Salty Dawg Rally.