Lessons learned along the way…I took my catamaran, Simba, from the factory in La Rochelle across the Bay of Biscayne down the coast of Portugal to Lisbon with two others aboard—my friend Lou and Capt. Florence—for a shakedown cruise. Capt. Flo and Lou got off the boat in Lisbon, and from there on I was alone.

Lessons learned along the way…I took my catamaran, Simba, from the factory in La Rochelle across the Bay of Biscayne down the coast of Portugal to Lisbon with two others aboard—my friend Lou and Capt. Florence—for a shakedown cruise. Capt. Flo and Lou got off the boat in Lisbon, and from there on I was alone.

During the next 10 months, I singlehanded Simba across the Med to Turkey and spent several aimless months sailing the Aegean and the Adriatic. Along the way, I like to think I learned a few valuable lessons.

1. DO IT IN A DAY

Crossing the Med can be mostly done in long day sails. After Gibraltar, I only sailed overnight on a few occasions: from Mahon in the Balearic Islands to Carloforte, a small Island and protected harbor off the Southern cost of Sardinia (196 nautical miles); from Cagliari in Sardinia to Marsala in Sicily (180 nautical miles); from Syracuse in Sicily to La Castella, halfway along the boot of Italy (140 nautical miles), then 148 nautical miles to Kassopei, a small town on the north coast of the Greek Island of Corfu. Once in Greece, the islands spread from the Ionian to Turkey. That was it for me to cross the Med. Sure, the day sails on occasion meant leaving at first light and arriving at dusk, but I never arrived at night and had no desire to. It was surprising for me that so many destinations were within a day’s journey.

2. PICK UP THE PHONE No one answers the VHF radio. I understand this is an overstatement, but entering harbors and contacting marinas was usually a one-way conversation, whether it was with the bridge operator in Levkas, the marina at Rota or the marina north of Dubrovnik. It seems most of the locals use cell phone when getting in touch with marinas. I was doing donuts at Zea marina in Athens for 20 minutes, calling on the recommended VHF channels—no answer. I had reserved a slip for a week using the Internet. Finally, a couple of staff showed up in a skiff and led me to my assigned berth. At the registration office I asked why there was no response on the VHF and was informed that I should have just called. I thought I did? Nice marina, by the way.

3. REMEMBER: BEGGARS CAN BE CHOOSERS For shorter stays, I found it was better to arrive at the marina of choice late in the day, tie up at the reception or gas dock, buy something (if possible), then walk into the reception area and beg for a space for the night. It is much harder to refuse a desperate man in person. In Spain, where there are few natural harbors, I was about three miles out and began to radio (yes, via VHF). This time I got a response, but not the one I wanted. There were no berths for catamarans. I pleaded and told her I could stay at the fuel dock and would be gone by first light—still negative.

It was late fall, a season not of high demand, and this was my first experience of “cataphobia”—a revulsion of wide boats. Somehow marinas believe that a cat is actually two boats and should be charged accordingly. My head was racing; I had at most two hours of light and no place to put the boat. I searched my charts and saw that there was another marina about 14 miles away. I would not repeat my mistake. I arrived, tied up, begged for a space and was never refused again. This was true only for overnighters; when staying longer in Gibraltar, Palma and Athens, I would e-mail my requests or try the phone.

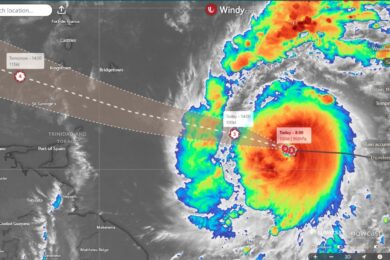

4. BECOME A MASTER OF COMMUNICATION Communications was a dilemma. Cell phone rates from Europe to the States are outrageous, and reliable Internet access could only be attained through local networks using USB air cards. This being said, everywhere is different—Vodafone Greece will work in Croatia, but the roaming charges are extortionary. Getting reliable weather information is easy if you can go online, which required—in many cases—taking my laptop to an Internet café.

There are many great free and pay weather sites. www.passageweather.com, www.meteo.gr and www.predictwind.com were all helpful and mostly accurate. I used an Internet antenna to extend the range of my laptop. If I could get a hot spot and log in, it was magical, but that did not happen as often as I would have liked. Mostly, you need to go to a café with Wi-Fi and buy a coffee, get the password and log on. Skyping worked well with decent bandwidth and is cheap, cheap, cheap. Most countries have pay as you go plans, where you buy so many gigs of data. Technology is relentless, the world is shrinking and these problems are sorting themselves out.

Today, smartphones have global data plans that allow you to collect e-mails and surf. It is a labyrinth that needs research and patience. Laptops are essential for communications and as a backup source for navigation. I loaded up my computer with Offshore Navigator Lite—a basic map program by Maptech—then married it to a USB GPS, and presto! I had a chartplotter. Google Earth is a fantastic way to preplan your next destination by getting accurate information through satellite photography. You can lower the horizon and virtually enter your next destination, viewing the harbor and surrounding landmasses as if you were in a helicopter. Laptops can also become entertainment centers, playing DVDs or downloaded movies. I personally got through two seasons of 24.

5. TRAVEL LIGHT “Lighten the load” is my motto. People try to fit their house into their boat—just look at the water lines. You don’t need all that stuff. The deck doesn’t have to be cluttered with jerry cans filled with fuel and water. Most people have too many tools, too many canned goods. Keep it light and simple. Keep in mind that there are some things everyone should have.

At the top of the list, without any reservations, is an autopilot—the best one you can afford, installed by a factory rep and calibrated on the water. I rarely steered my boat—the autopilot is that good. Beware of surfing conditions, which is the only time mine lost its marbles. I would rather spend my time tweaking sails and navigating than sitting at the helm. Second, I suggest an AIS radar detection system. I was blown away with all the target information such as name of vessel, speed course, etc.

I found it especially helpful on one occasion to contact a cargo ship in order to identify myself while crossing south of the Straits of Messina. In traffic at night I got on the VHF radio (yes, the VHF) and called out the ship’s name that was given to me by the AIS; if I had hailed “cargo ship,” no one would have answered. But shout out the name of the vessel and they will respond. The ship turned on her deck lights and slightly altered course.

Not all ships have AIS transponders, so a mast-mounted radar dome and display are wise investments, especially if you plan to sail at night. Most fishing boats go where they want regardless of where you are; this is universally true throughout the globe, so stay alert.

Next, get a solar panel. Bigger is better, mounted somewhere out of the way to catch as much sunlight as possible. They are maintenance free and will help your electrical needs, though in truth conservation is also necessary. No blenders, blow dryers or microwaves unless you are at a dock plugged into shore power.

Finally, get some type of light wind headsail. Why motor going downwind? I see it all the time. Choose a small, asymmetrical spinnaker on a collared sock—the sock is the deal, so find the best. It makes deployment and retrieval so much easier.

6. BACK IT UP! It’s time to talk about Med mooring, that bass ackwards way they have of docking in the Med. At first it can be daunting. There are a few things you need: lots of fenders, patience, the ability to forgive yourself and the courage to do it again. I have personally provided comic entertainment on multiple occasions.

6. BACK IT UP! It’s time to talk about Med mooring, that bass ackwards way they have of docking in the Med. At first it can be daunting. There are a few things you need: lots of fenders, patience, the ability to forgive yourself and the courage to do it again. I have personally provided comic entertainment on multiple occasions.

First, practice going backwards as often as possible. Have fenders deployed on both sides of your boat and rig a fender aft on your transom. Look for the small opening—yep, the small one. Your neighbors will provide a runway and will be happy to help fend you off as you begin to back down towards them. Drop anchor perpendicular to your chosen spot; if not, you may cross anchors with your neighbor, which is very impolite, especially if he leaves before you. Tie off the windward stern line first, snug up your anchor and secure your second aft line. You are home as long as the anchor holds.

7. SELL HER, SAIL HER OR SEND HER Now the big question: If you get the boat there, how do you get it back home? One option growing in popularity is transportation via cargo vessel. At first, it sounded crazy and expensive, but the more I looked into it, the more I liked it; no wear and tear on your boat! I used Dockwise—they delivered the boat to Newport, RI and don’t use cranes. You only have three options—sell the boat in Europe, sail the boat across the Atlantic or put her on a cargo ship. It’s your choice, but you should explore all of the possibilities.

Bill keeps Simba in Newport, RI after cruising the Med for more than a year. Bill’s last boat was an F-27 trimaran, which he used to cruise the Bahamas, Mexico, Belize and Guatemala. Bill has written articles for several magazines and is a media producer concentrating on streaming video clips of sailing events and travel destinations. Visit vimeo.com/album/246410

Bill keeps Simba in Newport, RI after cruising the Med for more than a year. Bill’s last boat was an F-27 trimaran, which he used to cruise the Bahamas, Mexico, Belize and Guatemala. Bill has written articles for several magazines and is a media producer concentrating on streaming video clips of sailing events and travel destinations. Visit vimeo.com/album/246410